“You know a book has you firmly in its grasp when a flight from Sydney to Brisbane goes by in what seems like minutes. ”

“This book is about joyful, puzzling absurdity, about unexpected tenderness, about loss at its most profound, and the line between forgivable and unforgivable flaws in the people we love.”

“The book may no longer be addressed to the baby girl she gave up all those years ago, but it is a letter of great beauty to her all the same.”

Writing For a Girl

“I have a writing table here at the farm, simple pine boards on tube-steel legs on the veranda of our cottage. The table overlooks a hillside at the bottom of which is a deep dam where we found dragonflies such as I haven’t since since my childhood. ”

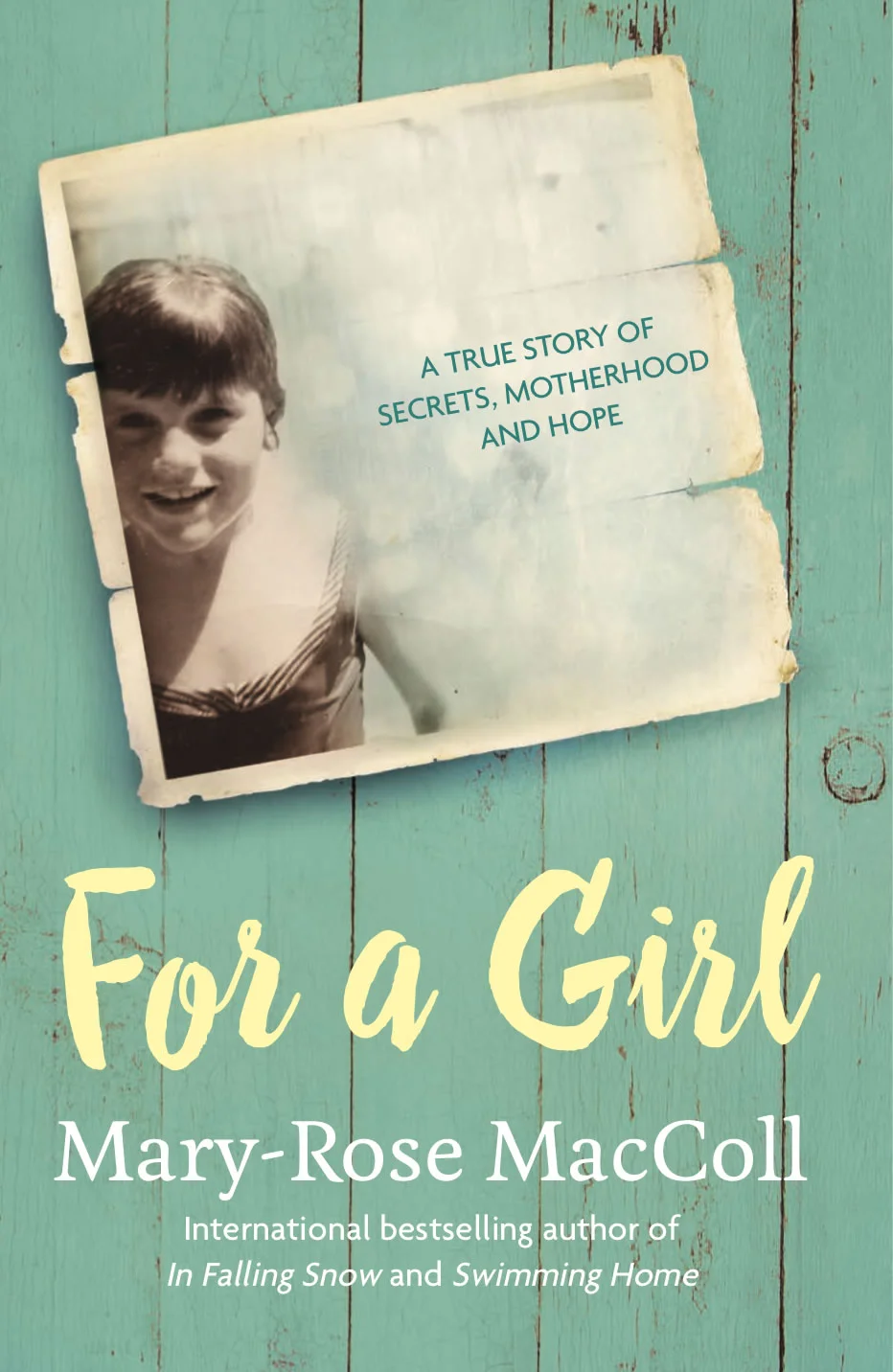

For a Girl is about secrets and the harm they’ve done to me and my family.

After my son was born, long-buried secrets from my young life came up to the surface. I stopped writing altogether. When I started again, at first I didn’t know what I was writing.

I went to Byron Bay and stayed in a cottage on a farm above the sea. Early mornings while my little son slept, I began to pull my writing together into the book that became For a Girl.

In those weeks at the farm, for the only time in my life, my writing came from somewhere beyond me, somewhere better than who I am. I found, not forgiveness, but beneficence which must come from somewhere else, from the Universe that offers beneficence.

If I sit quietly sometimes, I can be back in that place, where everything is exactly as it’s meant to be.

Extract from For a Girl

“I have a photograph of a girl of ten. She is standing by the convent pool she swam in every Saturday of that summer, in togs with a striped border I don’t remember owning. She is in the left of the frame and the background is an overexposed blur of water and the shapes of children. Her face is brightly white except for the freckles scattered over her nose and cheeks. Her hair is stuck to her forehead. She is grinning, saying to you, the observer, ‘I am here.’”

When our son Otis was tiny we lived in the gentle university neighbourhood of St Lucia in Brisbane, in a seventies townhouse with soaring ceilings and a balcony that overlooked a bushland park. Two frogmouths, mother and baby, spent their days in the tree outside Otis's bedroom in his first months in the world. Frogmouths are nightjars, related to owls, wise. I thought they could keep him safe.

On weekends, we'd put Otis in his all-terrain stroller and walk along Hawken Drive to the university for gelati from the Pizza Caffe above the Schonell Theatre. One Sunday, when Otis was not quite two, we’d met up with my husband David’s younger sister Lisa who was off to London to live. We’d had our gelati and Otis had coated his shirt in chocolate and mango. Now he was running around on the grass.

When it was time to go home, I called Otis and then, when he didn’t come, chased after him. I picked him up under the arms, his little legs still running through air in the way of busy toddlers. I sat him in his stroller and rolled up his shirt, the gelati now melted and cold. I strapped him into his stroller and he screamed.

At first I thought he was objecting to the restraint and I started to be stern. I wanted Lisa, who’d just finished a PhD in psych, to think well of me, to see me as a mother who set limits. Then I saw I had pinched his belly in the stroller clip. I undid the strap and picked him up and held him. He cried for half an hour. It left a claret-coloured bruise that lasted two weeks.

When we arrived home, I went upstairs to the bathroom and shut myself in. My right leg was shaking, the long thigh muscle in painful spasm. I slumped against the door to keep myself upright. The shaking spread to my pelvis, belly, left leg. I fell to the floor. Noises came from me, a low moan, a louder cry. My teeth were chattering, making the cries come out in an odd staccato. If it weren’t so terrifying, it might have been funny.

David knocked on the bathroom door to ask what was wrong. I had been quiet on the way home. I told him to leave me alone. I screamed at him to leave me alone.

After some time—I don’t know how long—I came out of the bathroom. I had no idea what had happened. The next day, I felt as if I’d run a marathon. Every muscle in my body ached.

In the weeks that followed, I told myself I’d been upset because I hurt my little boy. Any mother would feel bad about hurting her child. I told David. I told friends. You know what it’s like being a mother? I said. They didn’t quite understand, I could tell. They had felt bad for accidentally hurting their children but not like this.

~~~

When Otis came into my life, I understood abundance. His birth: I have never felt so powerful and exposed and exultant. David was there, my friend Louise. Afterwards I was buoyed by a community of friends and relatives who shared in our joy of new life; even people we hardly knew looked upon us with that same joy in their own eyes. Otis was perfect and he made me feel perfect. Nothing of the drudgery of the weeks and months that followed could extinguish that light of joy, and whatever I have faced since cannot touch it. In Otis’s first months in the world there was enough joy for a lifetime.

At the hospital where I gave birth, I heard one midwife call to another that the woman in Room 2, me, was an elderly primip. Elderly is used to describe any woman over thirty-five—the obstetricians who make up these terms being noted for their sensitivity—and primip is short for primipara, from the Latin primus, first, and para, bringing forth. To those midwives, to most people I knew, I was a forty-one-year-old woman giving birth for the first time.

Gail Sher says that writers, by doubt, enter the way of writing. I wouldn’t have described myself as elderly at forty-one, and I wasn’t primiparous when Otis was about to be born. I had given birth twenty-two years before, to a baby I named Ruth. No one knew. Baby Ruth was a secret because of other secrets, much darker than the birth of an unplanned child in those disco days of the 1980s. When I pinched Otis in the stroller clip, baby Ruth came back, demanding to be grieved, and with her came the secrets I had kept for so long.

I am by nature a private person. Secrets are different from privacy. They are things you are forced to keep to yourself, by family, friends, by your own shame. Secrets like these come to the surface one day and demand an airing. If you don’t allow them air, you will not go on. They will drag you back down with them. You will die, slowly or quickly.

If you allow them the air, bring them up into the light, they float away.